Common lakes | dual channel Audio-video INSTALLATION | 2021/2

3d Art: Kakia Konstantinaki | Text: Stella Sideli | Composing & Sound Design: Jacopo Salvatori

This PROJECT is kindly supported by RESPONSA Foundation

with special special thanks to; ARTIS, TBA-21 Academy, and Ocean-Archive

Common Lakes - Polifonia Mediterranea

〰️

Common Lakes - Polifonia Mediterranea 〰️

Polifonia Mediterranea

Introduction text written by Stella Sideli to Common Lakes, by Gili Lavy

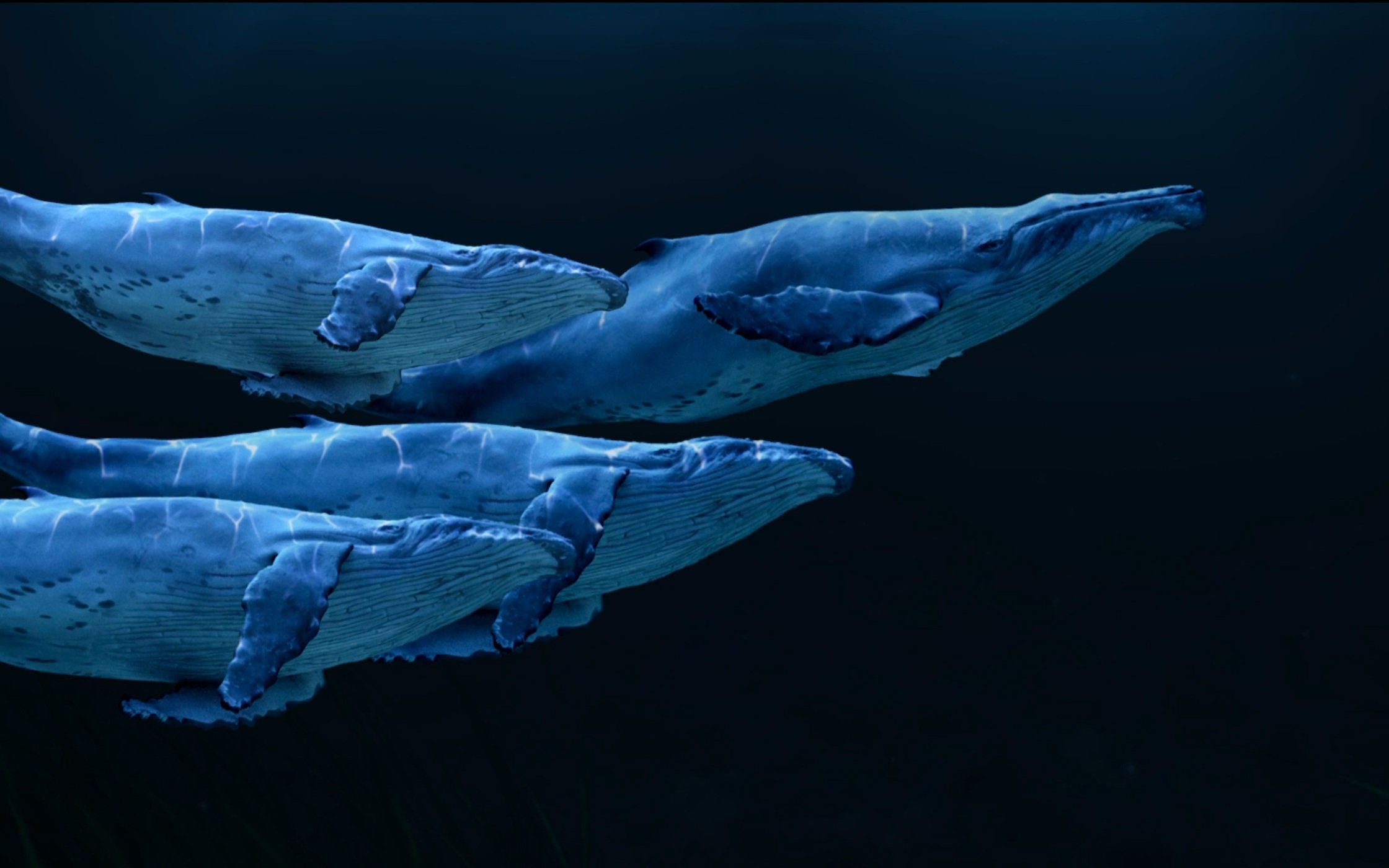

Whales are sacred, majestic marine mammals.

They have a mysterious Sagan-like connection with the earth, the sun and all the cosmos.

They have the largest heart in the animal kingdom.

A 180 kg weighing giant heart, only beating twice per minute.

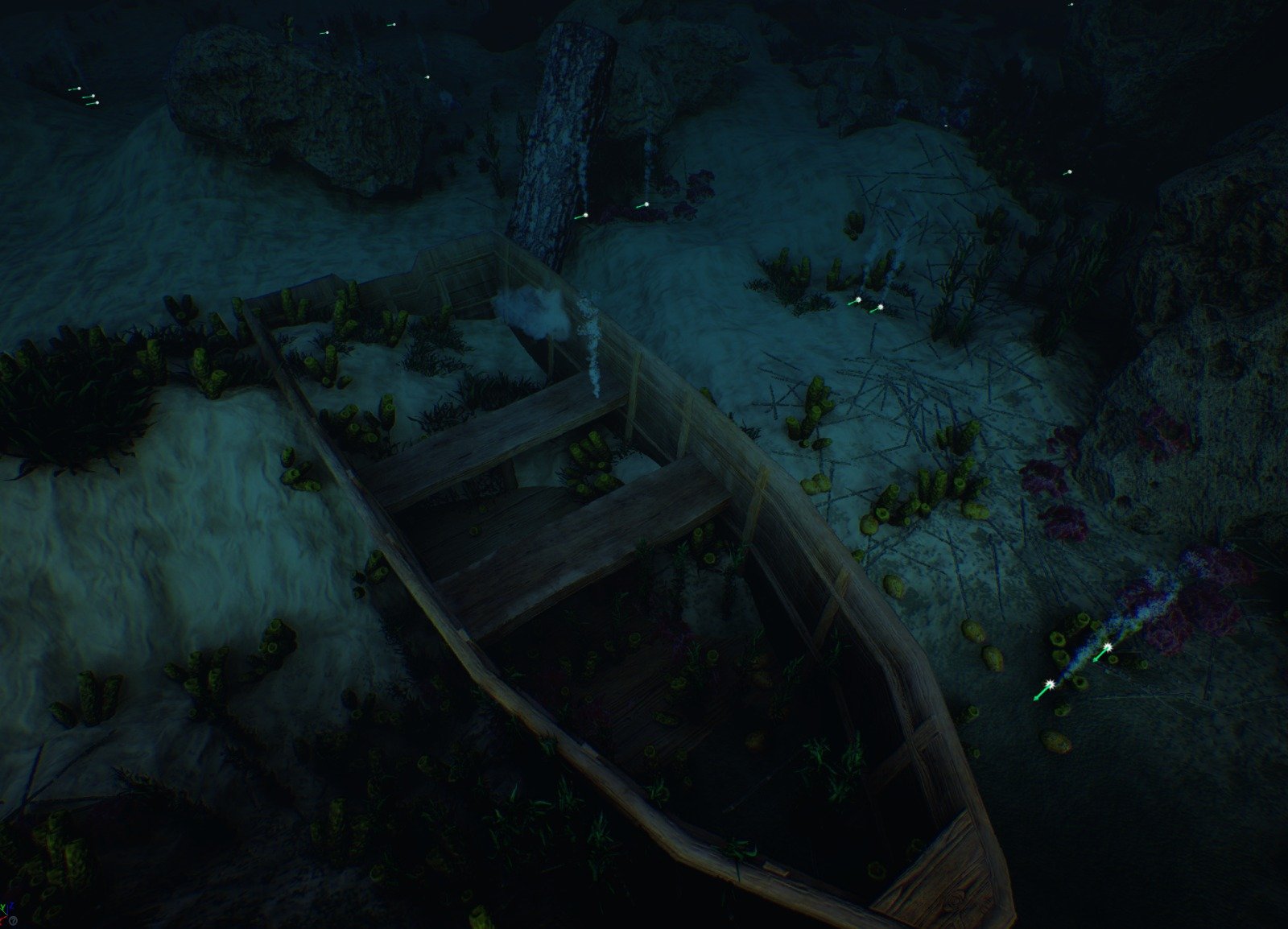

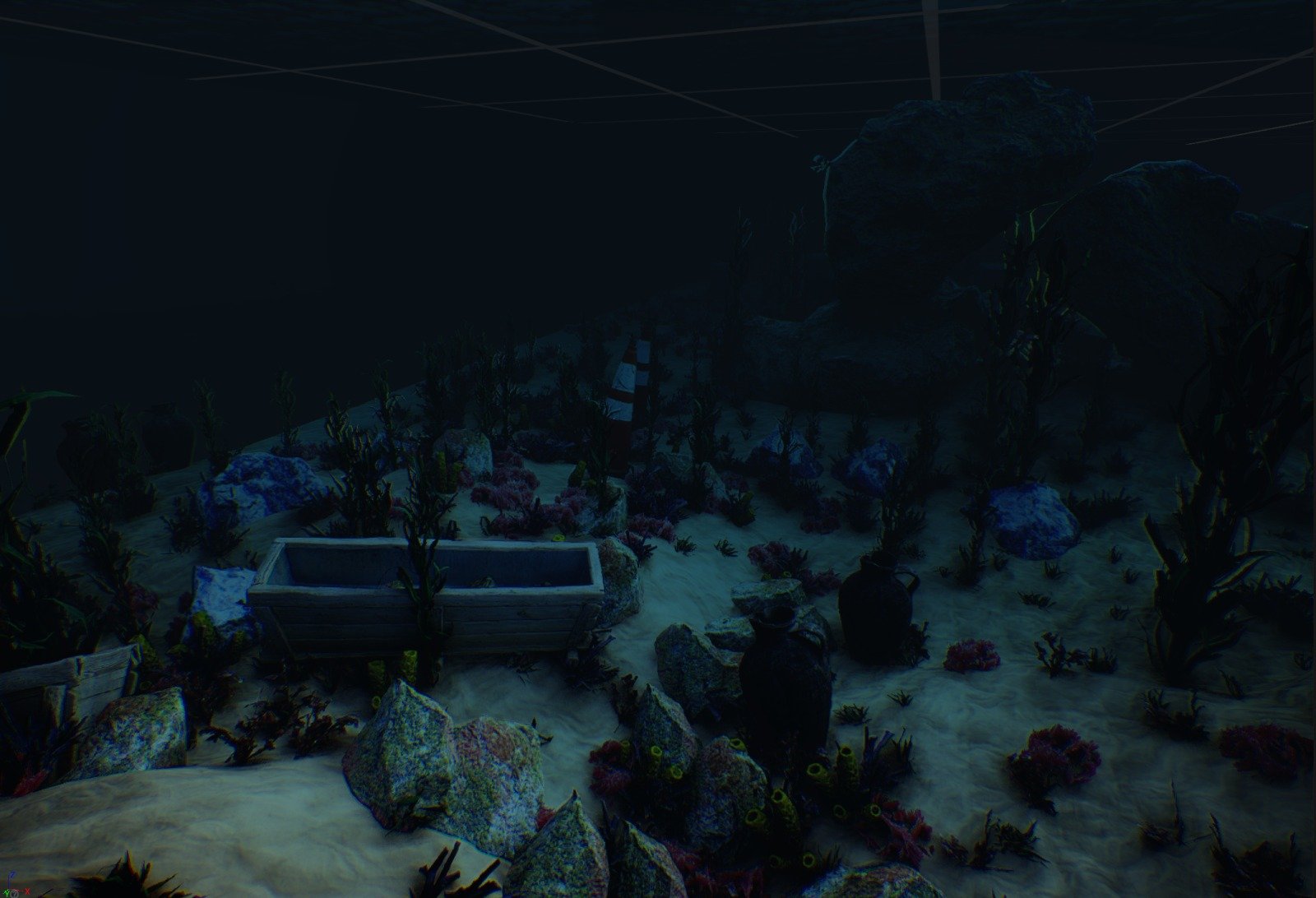

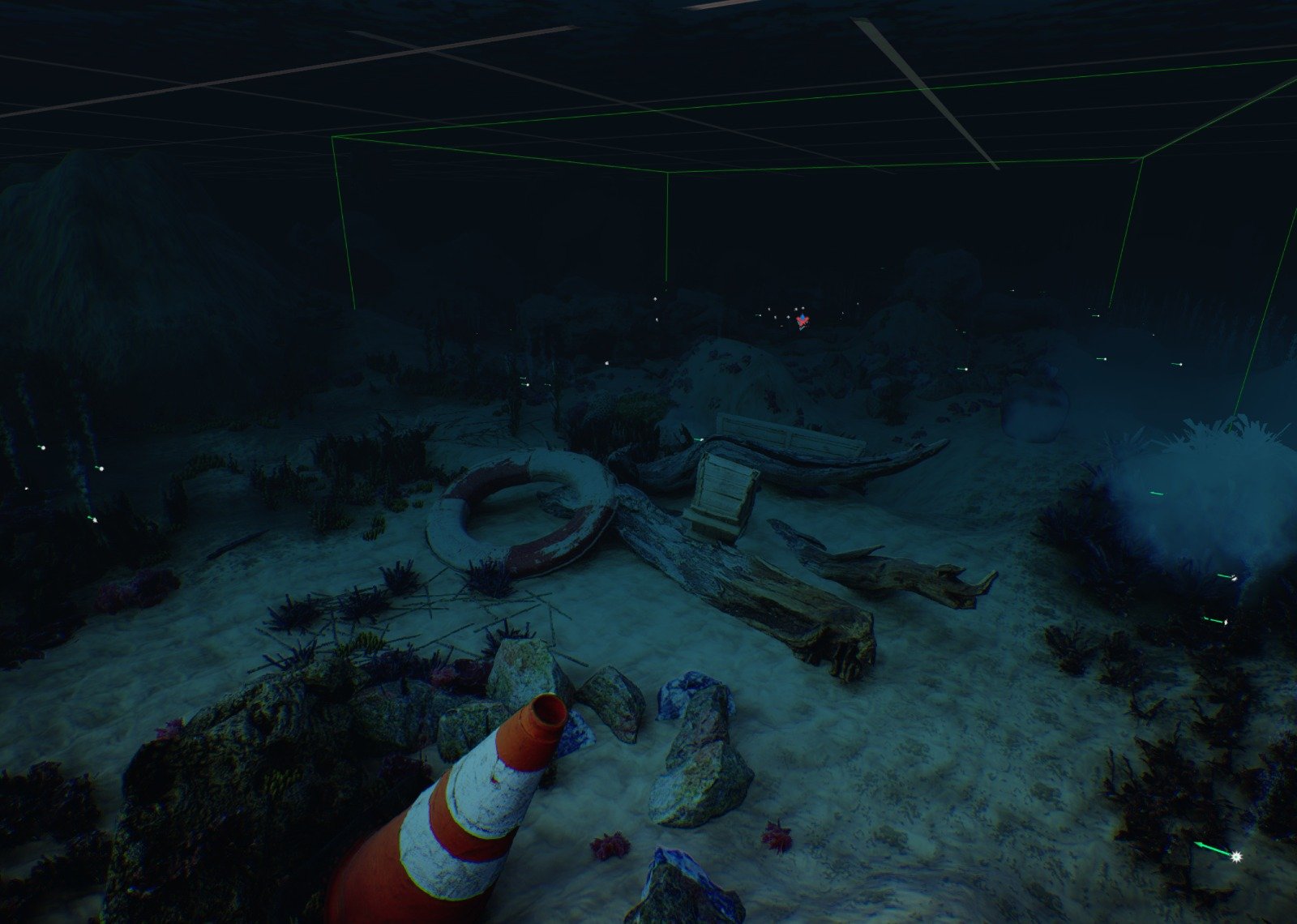

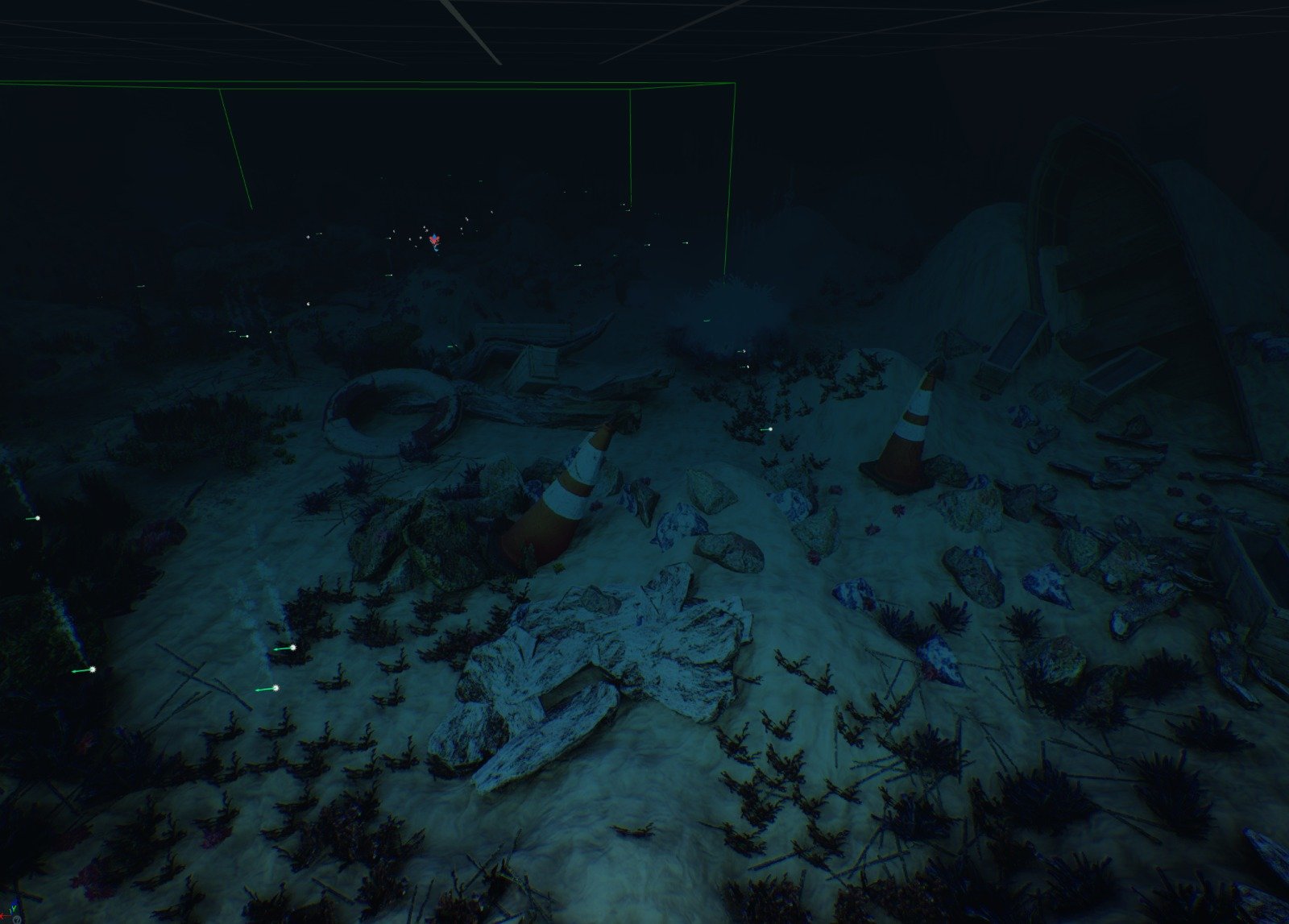

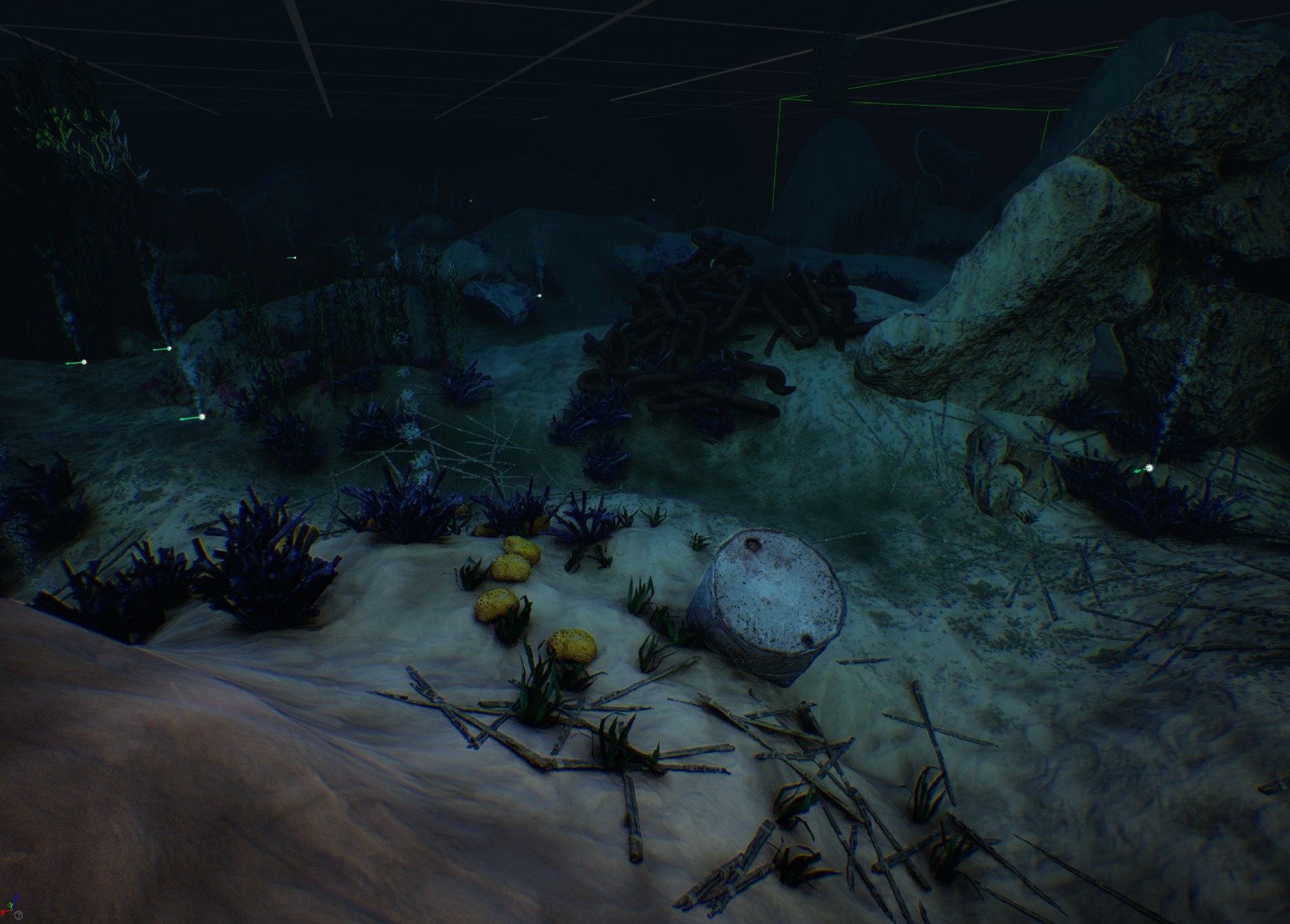

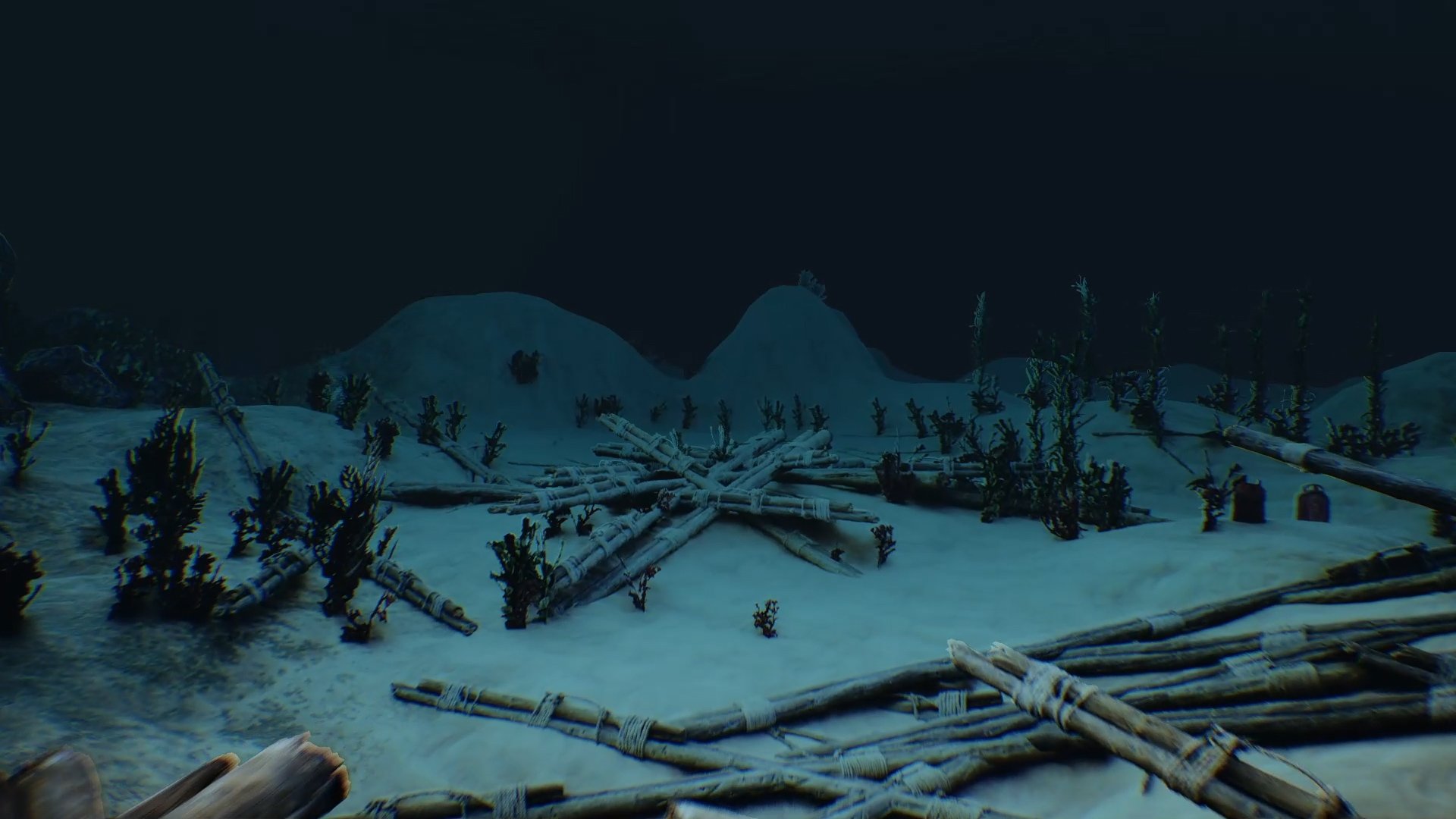

When we approach the body of work Common Lakes for the first time, we find ourselves quietly exploring the viscera of the ocean, almost enchanted by this immensely slow, deep sounding, huge beating heart that we can't really hear but which somehow articulates the journey.

Both in the video work (Common Lakes) and in the sound work (Common Lakes: whales pod crossing the Mediterranean waters), we follow a pod of humpback whales underwater, inhabiting the Mediterranean Sea. Humpback whales are usually found in the Atlantic Ocean rather than in the Mediterranean; however, it is known that it’s all one ocean. As a matter of fact, the Mediterranean Sea receives a continuous inflow of surface water from the Atlantic Ocean. After passing through the Strait of Gibraltar, the main body of the incoming surface water flows eastward along the north coast of Africa. This current is the most constant component of the circulation of the Mediterranean. It is most powerful in summer, when evaporation in the Mediterranean is at a maximum. This inflow of Atlantic water loses its strength as it proceeds eastward, but it is still recognisable as a surface movement in the Sicilian Channel and even off the Levant Coast. A small amount of water also enters the Mediterranean from the Black Sea as a surface current through the Bosporus, the Sea of Marmara, and the Dardanelles.

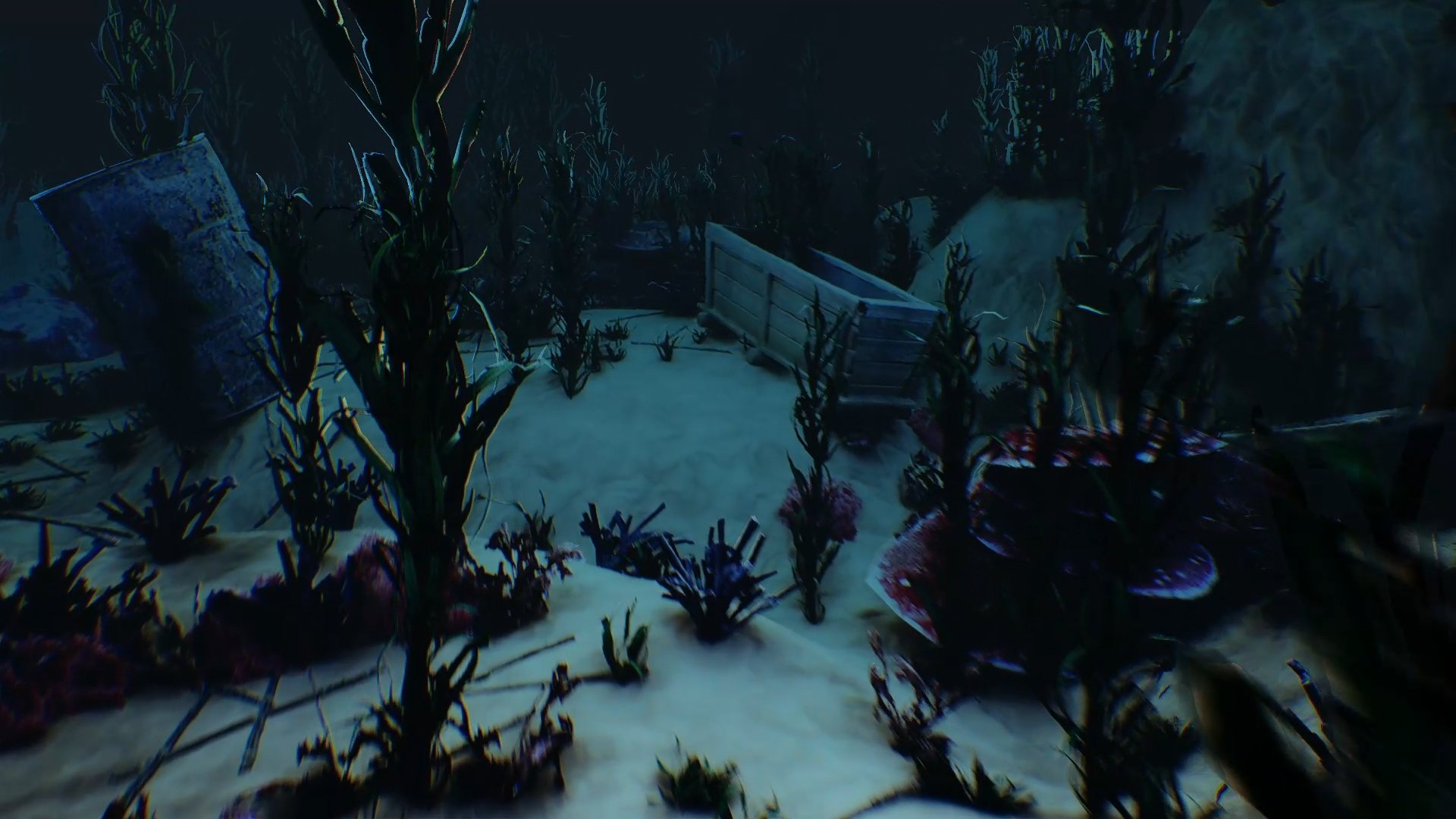

That’s where Lavy brings us, passing through the Central Mediterranean Route, which is the most dangerous and deadly migration route in the world; through the north coast of Africa towards the soon to be built 3 km long floating sea barrier between the Aegean Islands and the coast of Turkey, blocking migrants from reaching the Greek islands; and through the eastern Mediterranean Sea, where the world’s deepest oceanic crust lies— a 340 million year old seafloor bit in the vicinity of the underwater barrier between Israel and Palestine that blocks the surface by the coast of the Gaza strip.

In this long journey, water is the only constant: while everything changes, water is still there, cradling and connecting all stories, experiences and bodies on each side of a barrier. This is certain. As if it were even possible to conceive how a liquid, fluid, formless mass of water could hold a rigid body, a barrier, and let itself be neatly separated in two parts by it. As if a barrier underwater were not a membrane. As if water were not a geopolitical archive of populations, identities, narratives, memories, physical marks and tracks of anyone and anything trying to cross, reach, dream, and rebuild.

In the context of this work, “Archive refers to water’s material capacity for storage and memory. Not only are flotsam, chemicals, bodies, detritus, sunken treasure and other chronicles of our pasts harboured in the ocean’s depths; water, as various oral traditions show, is a literal container of story and history that serve collective cultural remembrances.”

As a matter of fact, while we follow the whales pod on their journey, this sense of collectiveness unfolds into a polyphony on various levels. It’s perceived in the choral speaking of the whales; the many views on the underwater environment; the presence of many histories in water— past, present and future, including a kind of genesis, a land without sea or, perhaps, the end of existence; a memory of events. We feel them and hear them, in water, the many voices of the Mediterranean. They compose a ballad, a song, a choir, a madrigal, a polyphony made of dissonances: of voices that are not always harmonious or coexisting, voices that tell stories of violence, grief, hopelessness, hope, faith, bravery, displacement. Voices that dominate, rule and police others, voices that whisper, pray and comfort.

The work articulates itself in the tension between states of liquidity and states of rigidity.

It aims to unpick that binary by connecting seemingly opposite terms eg. land/water or liquid/solid, which otherwise respond to logics of exclusion and separation, especially in the context of such a complex reality like the Mediterranean one.

Common Lakes invites us first to understand the Mediterranean as a liquid network of multiplicity, animated by the interrelations of all its inhabitants (human and not) and all its (hi)stories. While this is a main point to the body of work, another side of the story that emerges the more we are submerged into the depths of Common Lakes, is the idea of a ‘solid sea’— a hard, solid space, articulated by precise routes that move from equally defined points. From Valona to Brindisi, from Malta to Portopalo, from Algiers to Marseilles, from Suez to Gibraltar’, solid sea is a web of geospatial intelligence, comprised of remote sensing devices, satellite imaging, real-time tracking technology, border agencies and anti-immigration missions, intensely dense and layered planned migrants trajectories and circuits of territorial surveillance.

And just as it feels like we are about to decipher this movement, grasp this osmosis between different states of being (sea), then, another layer in the work manifests itself.

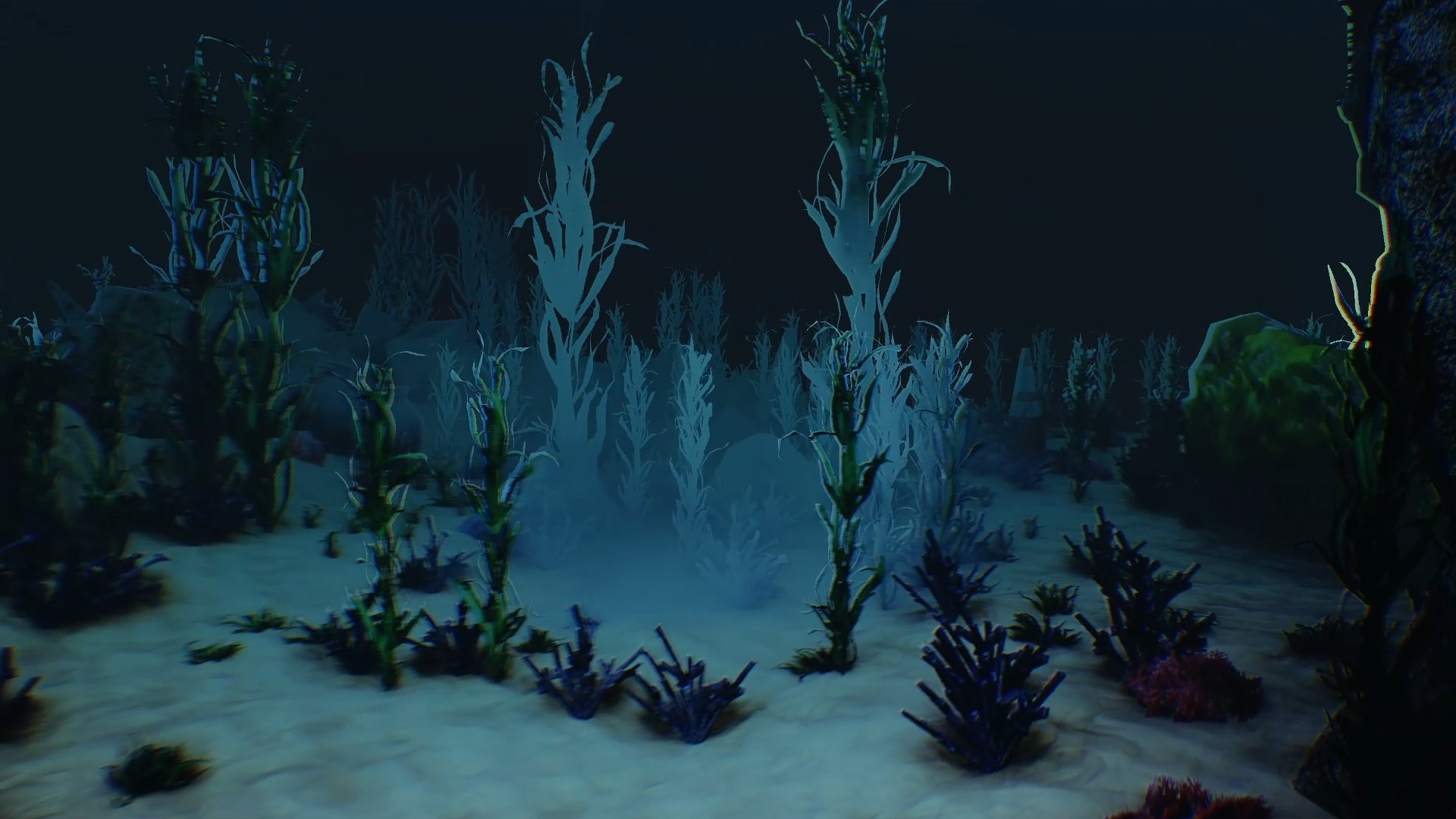

It’s a realisation that catches us by surprise, especially in the sound work: the Mediterranean is colourless.

It has turned its kaleidoscope-like colours into an indistinguishable colour, and the whales are witnesses to that change, throughout the years. Listening to them, we understand that the non-colour is all the tones of identities crossing the sea together, cultures, geological soils, geographic regions, historical phases, languages, religions, micro-climates, winds, crops, bodies altogether.

In figuring this, the feeling of solidity breaks again, (literally) dissolving itself back into fluidity one more time.

Thinking like water takes some energy, demands for a full restructuring of our way of understanding things and creating knowledge. The work attempts to do that by means of ‘diffraction’— the moment of insight that happens before affection, the process of ongoing differences and emerging patterns as a critical practice of engagement. A commitment to understanding which differences matter, how they matter, and for whom. Water does not allow for complete separation and rupture.

It’s in this formlessness, this constant change of perception of own essence, that potential lies, in water: this way, the liquid has become a space to imagine possibilities, hope and heal.

https://www.medqsr.org/mediterranean-marine-and-coastal-environment#:~:text=Today%2021%20countries%2C%20with%20surface,Syria%2C%20Tunisia%2C%20and%20Turkey.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/oldest-bit-seafloor-discovered-mediterranean-180960153/

http://s3.amazonaws.com/arena-attachments/1906530/29d7f149a8903b0fab4c7580a6461130.pdf?1521279845; See also Jody Berland, “Walkerton: The Matter of Memory” ; Janine MacLeod, “ Water, Memory and the Material Imagination”; and Peter van Wyck “Footbridge at Atwater.”

https://prod-content.ocean-archive.org/private/eu-central-1:12102e0b-bb96-42f0-9d3c-1df78ee120b2/418b7876-0b02-4d53-b0c4-38683f95c14b/a3bc3470-9c18-11ea-aa9e-ab67243a20af-Di%20Maio%20Mediterraneo%20Nero.pdf

Borderscaping: Imaginations and Practices of Border Making, edited by Professor Gianluca Bocchi, Dr Jussi Laine, Dr Chiara Brambilla, Professor James W. Scott, 2015, Ashgate Publishing Limited, England (pp 148)

https://ocean-archive.org/collection/56

https://ocean-archive.org/view/1033

2007, Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway. Quantum Physics and the entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham and London: Duke university Press.